Hello everyone

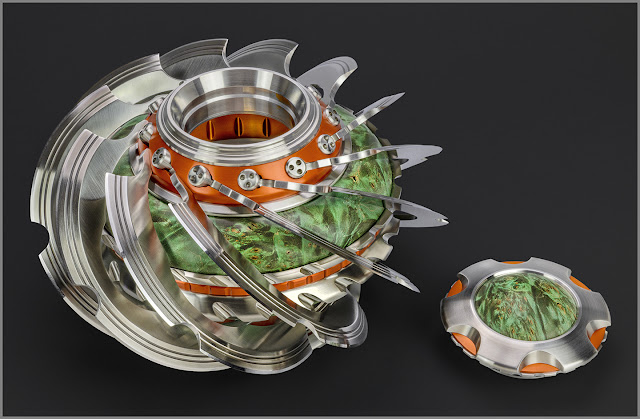

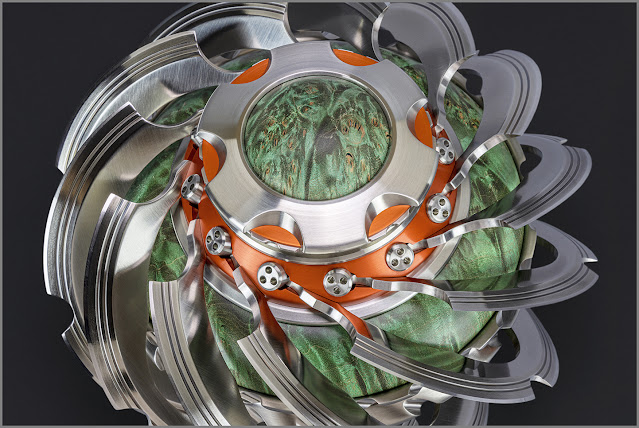

Today I have a piece to share that is four years in the making. I call it "The Sculptural Knife Urn" and it is the third work in my Sharps series of knife-centric craft forms. This is the last piece in this incredibly fruitful triptych of works. I dare say it has completely changed the path of my sculpture practice.

I can't talk about this project without partially re-stating the impetus for embarking on this project. It has been helpful revisiting my thesis with each installment, as it has allowed me to chew on my original assumptions and reframe them in light of new developments. So for those who like my longer posts, this is one of them.

The industrial Arts as Muse:

I'd hoped this fascinating tangent into knives and craft forms would help me tease out the interconnected nature of various industrial crafts. As I have tried to understand my relationship with my process, I have often turned my attention to other craft traditions such as ceramics, glass, and wood-turning. I've looked for parallels to how each of those practices transitioned from the factory floor to the artists studio–so that I can better do the same with the medium of machine work.

In each of these crafts, I found a remarkably similar story and I was moved to try and combine influences from all of them into a single series of works.

On reflection, I've come to realize this project isn’t really about knife making–it isn’t about vases, bowls, or urns either–it is about the state of craft as we find it. It is an appreciation of the idea that craft isn’t a rest-home for idiosyncratic or cast off processes, or where practitioners of defunct trades go to retire–it is a natural step in the material progress of our species.

Craft, whether part of the fine art landscape or somewhere else along the spectrum of utility and decor, is an important part of how we innovate to solve tangible needs. When material processes are brought into being, usually through the sciences or engineering, their uses are narrow and specific. But when the technology around that process is sufficiently advanced (or even obsolete for industrial use), it is artists and craftspeople who help flesh out the myriad alternative ways in which that process can be applied.

Artists are the ones responsible for transforming material innovations into cultural innovations that more broadly influence a society.

I talk a lot on this blog about how using modern machine tools to make art is a relatively new phenomenon, but I don’t think I have accurately portrayed what I mean by that. Indeed artists have been employing machine tools to produce various kinds of artwork for decades–a century or more even–so I should clarify what I mean when I say that machining–as a vocation–is becoming a new art form.

While the tools I use have been employed in the production of fine art – through various fabrication shops, organizational structures, and outsourced expertise–it is only just now beginning to exist as a studio craft movement in the same vein as other more established craft traditions–one who's practice is directly engaged with the medium rather than just being a means to an end.

What do I mean by that? I mean that the prerequisite for exploring a medium as a studio craft–by my estimation– is that an artist must be able to bring the entire enterprise under their control (one artist, one studio). In the most decadent way, every aspect of a practice must become available for creative appropriation, deconstruction, and exploration. I say this more as an aspiration than a hard rule, but a solo artist practice is one of the few settings that provides the freedom necessary for the uninhibited level of investigation it takes to create artifacts that both influence, and distinctly represent, a medium.

Personal access to modern forms of metalworking equipment–the kind that makes the most rigorous artistic exploration possible–has been largely out of reach for most practicing artists until very recently. History has plenty of examples to demonstrate how a process blooms once conditions change, allowing artists to truly own the means of production, so let's use fine art glass as an example.

Decorative glasswork has been around for centuries, but for brevity I am skipping over the Egyptians, and Romans to create a slightly more contemporary example.

I think one of the better known glass makers from the turn of the 20th century is Tiffany glass. Louis Comfort Tiffany set up the Tiffany Studio in New York and produced a wide array of stained glass and other decorative glass designs. He developed a number of innovations in the science of creating glass and greatly expanded how it might be used for artistic purposes.

However, the structure of this outfit was as a design house and factory. It was run by teams of artisans and designers working to produce decorative and utilitarian pieces. There were plenty of successful attempts at art, but by and large it was a commercial affair that catered to a decorative class of collectors. The work was constrained by the socio economic guardrails of what a “collectable” glass object could be. In order to sustain the factory, the vast majority of its output was stained glass, lighting, vases, and the like.

Contrast this with the birth of the studio glass movement.

In 1962, on the heels of a boom in interest in the studio ceramics movement, Artist Harvey Littleton and research scientist Dominick Labine developed a design for a small and affordable furnace that could melt glass. This small advent removed the need for teams of operators as well as greatly reduced financial and physical infrastructure needs. It singlehandedly created the conditions for solo artists to bring the production of glass art directly into their studios. In the same manner as a painter might paint, artist were able to work freely with glass, away from outside eyes and commercial influence. This meant glass art could be practiced by one artist in one studio.

Glass art's popularity began to grow and this era saw an explosion in the creative output of artists using glass. The guard rails were suddenly gone and a piece of glass art could be literally anything (or nothing at all). Experimentation was rampant and this gave rise to the fine art landscape we see in glass today. Many of the examples of glass sculpture we see in museums were born out of this era.

However, the structure of this outfit was as a design house and factory. It was run by teams of artisans and designers working to produce decorative and utilitarian pieces. There were plenty of successful attempts at art, but by and large it was a commercial affair that catered to a decorative class of collectors. The work was constrained by the socio economic guardrails of what a “collectable” glass object could be. In order to sustain the factory, the vast majority of its output was stained glass, lighting, vases, and the like.

Contrast this with the birth of the studio glass movement.

In 1962, on the heels of a boom in interest in the studio ceramics movement, Artist Harvey Littleton and research scientist Dominick Labine developed a design for a small and affordable furnace that could melt glass. This small advent removed the need for teams of operators as well as greatly reduced financial and physical infrastructure needs. It singlehandedly created the conditions for solo artists to bring the production of glass art directly into their studios. In the same manner as a painter might paint, artist were able to work freely with glass, away from outside eyes and commercial influence. This meant glass art could be practiced by one artist in one studio.

Glass art's popularity began to grow and this era saw an explosion in the creative output of artists using glass. The guard rails were suddenly gone and a piece of glass art could be literally anything (or nothing at all). Experimentation was rampant and this gave rise to the fine art landscape we see in glass today. Many of the examples of glass sculpture we see in museums were born out of this era.

The story of glass art resonates with me because very similarly, and until very recently, artists looking to leverage machine tools and modern digital fabrication technology for the creation of art would likely have needed to rely on design firms, tech schools, and fabrication studios with teams of specialists who could assist in programing, running, and maintaining the machines that were beyond their experience and financial reach.

Like early glass factories– this limited access to tools has a way of constraining the way digital fabrication technology is used. Limited access can have the effect of relegating the artist to being primarily a designer, which places them in a more perfunctory role in the production of their own work.

Now don't get me wrong, institutional settings are perfectly appropriate for early education. Maker spaces, apprenticeships, and schools are important resources for developing a practice. Likewise, there will always be legitimate reasons for artists to share resources and hire outside experience for the production of work, be it for conceptual reasons, or practical constraints. But that is no reason not advocate for an ideal.

Every artist who is invested in directly exploring their craft, should strive for creative independence and plan their exit from institutional reliance as soon as it is appropriate. There is no substitute for owning and running your practice in its entirety. Anything that limits when, where, or how you can pursue an idea can be detrimental to your ability to create.

History backs me up on this. So seize the means of production and make it a conceptual part of your art.

I started out exploring modern machine work with an eye toward fine art sculpture, but over the years, pursuing work in the spirit of many of the studio crafts that have come before has also become an important part of how I define my work. So long story short, here I am with a razor sharp decorative urn made of machined knives and decorative hardwoods. A piece that is (somehow) supposed to embody all that I have said. Sheeesh!

I hope some of you will appreciate the nuance I have poured into a project like this, it is certainly what keeps me digging ever deeper into the possibilities of my craft.

Some additional thoughts: I want to close this out by saying that I try to be careful about subscribing to various dogmas. I have enumerated a very particular way of thinking about the evolution of craft. One that simplifies and ignores differences in geography and time (that is, people used tools and materials differently, in different places, at different times throughout history). In doing so I have no doubt implied that there is some greater value or purpose in creating “fine art” as it is understood in western culture. But this is not quite right.

I want to be clear that life is not as neat and tidy as the above summary–or art canon–depicts. Artists, designers and craftsmen will always fall along a spectrum in how they utilize tools, materials, and concepts; no doubt overlapping many different worlds during their lifetime of creating.

However, I feel it is instructive to think about the various stages that material technologies undertake as they move through a particular culture. Creating fine art is just one of a number of equally noble ends (like science) that help us to appreciate the means by which we express ourselves. How processes make their way from discovery, to utility application, to culture producer, to conceptual symbol for a unique moment in time, is a useful framework that can help us all make better work–whatever that work may be.

Technical Notes: In building this piece, I. was able to incorporate many of the techniques and processes I have been honing over the years. Most recent of those being the dyeing and stabilization of hardwoods.

After my experiment making several turned wooden bowls, where the incorporated woods were structural elements of the piece, I wanted to turn to a much more decorative approach. The green maple burl pieces in this design are not structural, but instead serve only as inlays and bosses. They function as allusions to other decorative elements I have admired in my research.

I am calling this third work an “Urn” but like most of my works, strict classification is neither easy, nor necessary. above is the earliest concept sketch for the whole series.

As you can see, as the project slowly progressed (less than one work a year) the deviation from my original plan became more and more severe. My original urn design (on the right) is completely unrecognizable from what I ended up creating. This is exactly as one should expect, as each work in the series added new information and challenges that needed to be incorporated.

My original urn design did have an interesting assembly mechanic, but perhaps I will use that somewhere else in the future.

This complex arrangement also gave me a small amount of adjustability to ensure the blades could be properly installed.

Which brings me to the blades themselves. I have tried to rationalize my use of razor sharp blades in various ways. Now that I am at the end of my journey, I think they need little justification. Their aesthetic contribution to the work is very evident in this piece. That they add a conceptual layer to the work is only a further bonus.

Sometimes you just have to try something because you can. In all my research into knife making, it always seemed like the smooth curved bevels on some blades might be achieved using a facing operation on a lathe. There is no reason to do it this way of course, and I have never seen it done this way. All the more reason to try it. So I designed the blade forms intending to try and turn the bevels on a lathe, which is a very unusual set up for a knife maker.

This process was pretty rough on the cutting tool inserts and many were chipped long before they should have. 440C stainless is a hard material, which does not lend itself to this kind of cut. But it actually worked! and the finish was pretty good. Who knows, maybe there are other ways to make knives on lathes.

Above is a process video that illustrates this turning operation for the blades (approximately the 13:25 mark). I tried to capture the bulk of the steps that brought this piece of art into being, but life in the shop gets hectic and I did miss a few steps. Some other video clips were lost due to technical issues. But all in all, it is still a great ride.

Anyway, I am glad to bring this tryptic to a close and apply what I have learned to new sculptural adventures going forward. Thanks for sticking with me for the long read. As always, comments and questions are welcome.

Above is a process video that illustrates this turning operation for the blades (approximately the 13:25 mark). I tried to capture the bulk of the steps that brought this piece of art into being, but life in the shop gets hectic and I did miss a few steps. Some other video clips were lost due to technical issues. But all in all, it is still a great ride.

One last thing that I have wrestled with over these three knife projects was the level of finish to apply to the blade forms. I have tried to approach their creation as a machinist would–as opposed to a blacksmith or knife grinder. To that end, I have eschewed the common practice of bringing the final knife forms to a very high mirror polish. There is some economy in doing this, but my primary reason for not doing so is because, over the course of my entire practice, I have found mirror finishes to greatly distract from seeing the form of an object as a whole (I have always preferred satin finishes or finishes with grain).

With a mirror finish one does not see the object, only the reflections around it (photography is also a nightmare). Likewise, even though I am a machinist that uses numerous automated processes, I have come to appreciate small bits of evidence as to how a part was crafted, such as fine turning marks you can only see under close inspection. Even with computerized tooling, each process has its own signature look if you know what you are seeing.

I think to most eyes, the difference will be small, but to me it is important that I can tell how each part is made, not by remembering, but by looking at it.