Not too long ago, I did a really fun interview with make magazine. In the article, I got to talk about my sculpture work, my experiments with 3D printing, and other digital aspects of my practice. I was also invited to give a little background on my blueprint drawings. From that

experience, and because I have been preparing for an upcoming exhibition, I

have found myself doing some additional writing on the topic of the schematics

I produce. I have been reassessing their evolution over the years; how they

have come from crude hand drafted pencil sketches to become highly refined pieces

of digital draftsmanship. I have been thinking about my early approach to them,

what they have represented to me along the way, and most importantly what

purpose they now serve.

To start, I think it is obvious that drawings of some nature

are necessary to flesh out my sculptural designs. To be successful at the highly

technical process of machining metal, a large portion of the work must be

extremely well planned. At a minimum, I must make drawings in some form in

order to make my primary sculpture work. But as has been established, I have

felt compelled from the very beginning to do more with them. My first layout

for a machined sculpture was actually composed as an almost abstract geometric

drawing.

When I was first getting into this kind of work, my

instincts immediately led me away from treating my drafts as objects of mere

utility. I was never comfortable with the idea of divorcing them from the

conversation that I felt the finished work would go on to present. I always

found myself wondering, if the sculptures were supposed to be the primary focus,

then why was I giving so much attention to drafting detailed renderings of my

work? I would spend hours meticulously laying out the lines on sketches which

were never intended to be seen by anyone but me? I always had the nagging question in my head "If a sloppy unorganized

drawing would suffice, why go further?"

(See working sketch image below.)

Early on, my answer to this question was one of affection

and integrity, because I cared about the process. I was moved to explore the

drawing methodology like I was drawn to exploring every other facet of what it

takes to bring one of my machined metal objects into this world. It was about

not taking any of the steps for granted, and giving each phase of the process a

fair chance to exert its proper influence on the design. It was simply fidelity

to ones craft.

Over time however, I was inspired to expand my idea of what

Drafting and CAD work could be. Did it just have to be a drawing that was

accurate? Could it also look interesting for its own sake? Were there other

aspects of this approach I was missing? Could they be considered fine art? It

was this sort of searching that initially led me to think about ways I could

print my drawings in a non-perfunctory way. This ultimately led me to seek out and

acquire a blue print machine.

I reasoned that, if I was going to print and present my

drawings as works of art, I did not want to simply have my drawings printed on

a modern ink jet, I wanted a process that was as involved as the rest of my

work. Something that required some sort of technical knowledge related to what

I was doing. Blueprinting, while admittedly novel, also served the function of

providing a tactile way of realizing an otherwise purely digital aspect of my

work. As a sculptor, tactile experiences are never to be underrated, and so it

was an experiment I undertook with the hopes that it would contribute something

of substance to the work, rather than just being a means to an end.

Initially, making blueprints presented a number of

interesting challenges. The process of running an ammonia spewing, UV powered

printing operation that was sensitive to dust, light, temperature, and the

opacity of paper itself, provided plenty of adversity. Managing all of those

logistical concerns, suggested new ways of thinking about making the drawings,

which influenced how I implemented their visual appearance. All of this, if you

follow my work, is the kind of form and function duality I often seek out in my

sculpture. This in turn, helped to further my conception of my schematics as art

objects in of themselves. It all seemed like a good fit, and I am happy with

the results I achieved during this experiment.

But unlike machine work, once the initial constraints of

printing were explored, and the novelty of using an antiquated printing process

wore off, there seemed little new territory to move into. I was left with a

somewhat limiting set of parameters under which I could work and there was

little I could do to expand on it. The machine itself was admittedly old and

finicky, but the paper was also an issue. The largest I could print on my setup

was 24x36, which prevented many of my drawings from being to proper scale. Additionally,

the paper is fast becoming extinct.

When my initial supply of paper ran out, I had to do some

serious digging to find more. I ordered through three different manufacturers

before I was able to obtain a supply that was neither too old, nor too damaged to

use. The usable paper I eventually ended up with produced a very different

shade of blue than my original stock. Gone was the rich cobalt blue of my original drawings, and in

its place, was a less acidic, denim blue color. In some ways, it makes no

difference; the new color still looks nice, and the inherent variability of the

end product was part of what drew me to blue line printing in the first place. It

was all part of the fun.

Now to be fare, all of the obstacles listed above could be

overcome, I could make my own emulsion and paper, and I could invest in

enlarging the scale of my printer. I could even outsource the creation of the master

prints. But the ordeal I undertook with the paper made me realize I was

expending a lot of energy on things that had very little to do with the actual

core of what drew me to making these drawings in the first place. I felt like a

rethink was in order.

So I asked myself, “blueprint making aside, what was I trying

to do with these drawings?” Was I really just riffing off of a pre-existing

aesthetic? I have seen many artists use the

technical drawing as a motif for creating art: From whimsical juxtapositions of

the rigid nature of schematics with more free-form imagery, to the meticulous

design of completely fictional worlds and devices. All of them interesting in

their own way, but they all seemed to diverge from what I felt I was doing in

one very substantive way. I was

not just copying the look of drafting; I was emulating its substance.

Through all of my intention to explore drafting as a means

of creative expression, I felt the one thing I could not compromise was their

accuracy. No matter how I wanted them to look, the thing that underpinned the

rest of my decisions regarding their creation was my desire for them to be a

reference for the sculpture from which they were derived. Although limiting in

a lot of ways, the relationship to the sculpture work was something that had to

remain intact. Once I thought about them in this context, their function became

clearer.

That the works never strayed into fictional territory, that

they never diverged from their original function to become their own creature

entirely, was not for lack of vision. My insistence that the drawings be

visually compelling while always communicating real information about their

parent sculpture had to do with the fact that they represent something the

sculptures themselves cannot convey in their finished form.

So then, what purpose do they serve other than as a

technical document? Lets look at my sculptures for a minute to see if we can bring

the two together. In the context of the drawings, what is it about my sculpture

work that makes it different from a lot of other sculpture in that it would

benefit from a schematic accompaniment? Even sculpture fabricated by digital

means?

If I had to boil it down to one primary distinction, it is

this. Unlike a woodcarving, a bronze casting, or even a 3D printed work, which

are all comprised of a single uniform material, my works are fundamentally

engineered. Where as the former

represents a type of statuary, primarily meant to be appreciated for the superficial

form or qualities of the material they are made from, my works are comprised of

many intricately designed and interconnected components, many with real

functionality such as clamping mechanisms or other fastening systems built into

there internal structure that, while not always evident in the finished

product, inform the look of the work they are a part of.

To say it another way, my sculpture works are largely about

their own construction. They are designed to convey something of the complex

array of process and mechanical qualities that go into their own creation. It

is a bit like writing a story about writing a story (which admittedly might seem silly to some) but it is an important aspect of what I think is so interesting about

how my works are conceived. They represent a type of Intentional design that

purposefully eschews a correlating end function. They are an exploration of a

process that is used to produce nearly every component of our industrialized

society, and so the works are constructed in a similar manner, to lend an air

of implied Utility. Even though they are static art objects with no function,

they are objects that resonate with an implied, if indefinable purpose. That is

one of the key contrasts I aim for with my machine work.

Communicating this duality between the inner workings of

each sculpture and its outward aesthetic function is something that is very

well suited to the drawings. Indeed much of the engineering and design elements

are completely hidden in the finished Sculptures, so the schematics are a

natural link between this conceptual facet of the work and the physical

implementation of the it.

With this primary function of the drawings now made clear,

it seems much less important that they be realized in a way that lends them

unique physical character that may detract from this function, or otherwise imbue

them with superfluous novelty. That

they illustrate the relationship

between the designed ideal and the workmanship that goes into creating the

finished object is enough to justify their existence in nearly any form.

I now see the drawings as a way of memorializes a part of

what is fundamental to my way of thinking about art that might otherwise be

lost.

So to bring this all back around, while I have not lost any

of my affection for my craft (which includes the drawings) I will no longer be

pursuing the blue prints in their current form. I am opting instead to print

them more traditionally so as to remove some of the limitations the blue line

prints have imposed. I want my schematics to continue to pull back the curtain

on the inner workings of my sculpture without compromise, and so I will be

moving forward with that as my primary concern.

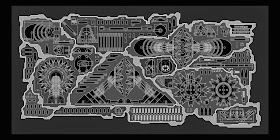

Above is an image of the newly printed versions that will replace the blueprints.

I am going to be doing a final print run with the remaining paper and supplies I have and the blue-line drawings will continue to be available until that stock is exhausted.

I am going to be doing a final print run with the remaining paper and supplies I have and the blue-line drawings will continue to be available until that stock is exhausted.

The new prints however, will be available very soon as full-scale

color prints . They will be printed on Dibond, which is a 3-layer rigid panel

with a plastic composite inside, and a layer of aluminum on each face. They are very light, extremely durable, and

produce a gorgeous matte finish. I could not be happier with my early test

prints and am looking forward to my first exhibition, with the new drawings

front and center very soon.